South North Griots Summit Team: Dwayne Morgan, Motion, Nth Dgri, Eddy DaOriginalone.

Saada STYLO reflects on a personal journey into the art and heart of Spoken Word in this exclusive blog post for the Canada Council of the Arts.

More than 20 years ago, youthful and thrilled by just about every experience, I lost in love. The pain of the heartbreak had me reflective, so I sought comfort in the writings of black poets, authors and folk singers. It wasn’t long before my pensive moods gave way to indignation and I put pen to paper to write my first poem, “Bittersweet Departure.” I was green, as was my technique. My words seemed tightly tangled and the sentiment flat. The poem remained inconspicuous within the pages of my closed notebook.

Then I watched Maya Angelou’s apostles describe how the span of their hips and the curl of their lips made them phenomenal and I, with a growing audience, was captivated by the poetic prowess of the spoken word artist.

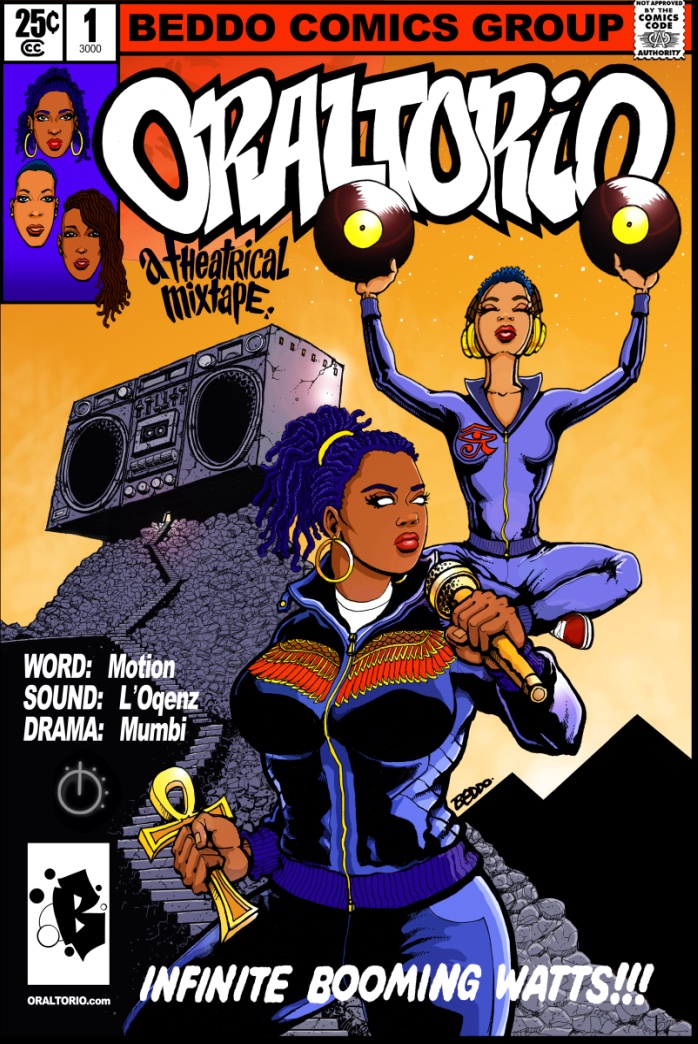

To understand spoken word is to appreciate how it is poetry constructed for flight. There is movement in its meaning and a lifting of its phrasing; so much so, members in the audience catch the cadence, sway to the melody, rise to the call, raise fists in solidarity and bow their heads in mourning. In a manner so quintessential to the concept of an artist’s call and response, we lend our ears and much more to spoken word artists. Theirs is a full-bodied, poetic expression that frees us from technique and formula and rigidity and rules and instead captures us in flowetry.

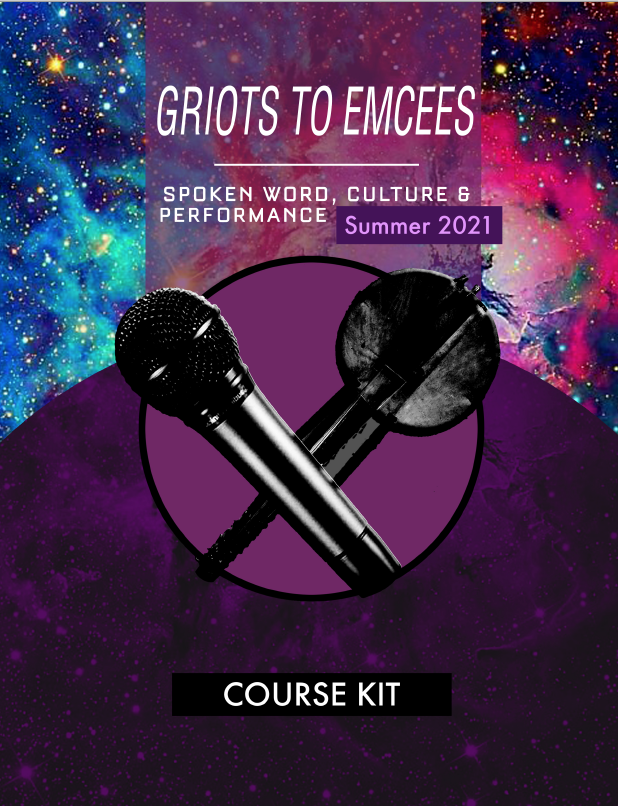

A gathering of Griots

Most artists and art lovers have access to a galaxy of cyber spaces formed to share what we think and how we feel. One useful tool for connecting is subjective thought, and how we express it can present an opportunity to expand and then elevate the discussion. I’m expecting that consciousness raising at the South-North Griots Summit on May 28-31 at Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre.

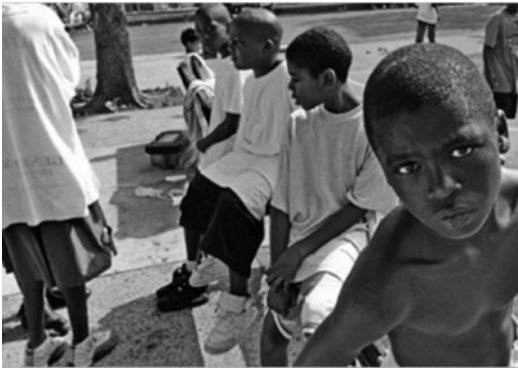

The 4-day gathering of wordsmiths from North America, the Caribbean and Africa at this city’s cultural hub is noteworthy. The artists who will perform and participate in panels have sparked a trail of personal and professional achievements. Their arrival at the Harbourfront raises Toronto’s profile as being a welcoming host to a movement of heroic writers performing poetry as they feel it.

Canada has a history of spoken word artistry; one that encapsulates slam contests and freestyling. But first there was dub poetry. There, as I imagine in the spirit of Trinidad & Tobago parang, words are gripped differently and restructured like instruments of sound connecting with audiences through utterances, beats, riddim, a snap, a stomp and a verbal massaging of Caribbean dialect passed on from Ancestral tellings. The delivery of dub’s mellifluous soundings intertwine with stories about hardship, integration, exclusion, actualization, celebration, growth, self-love and, yes, heartbreak experienced by everyday Caribbean women and men. Authors Karen Flynn and Evelyn Marrast describe dub poetry in a 2008 journal article, citing Jamaica as the birthplace for this movement of the working class and non-elites:

“With its emphasis on what Edward Kamau Brathwaite (1982) calls ‘Nation Language,’ dub poetry by its very existence challenges the hegemony standard English and the literary establishment; articulating the anger and despair of ordinary Jamaicans, it is necessarily protest poetry …”1

That protest caught and grew then migrated. Today, the tales are passed on and shared by a Canadian generation that honours its trail forgers George Elliott Clarke, Lillian Allen and the incomparable Louise Bennett; a cross-section of spoken word artists that birthed the new voices. They in turn use varying art styles to sound off about marginalization and the way it morphs into something else, posing challenges in the application of their craft.

A meeting of minds

Why a summit? I’m learning that the seeds for this type of artist discourse were planted by the Northern Griots Network (NGN), a collective of African-Canadian spoken words artists in collaboration with the Nia Centre for the Arts and the Harbourfront Centre. Back in 2003, the NGN organized a series of poetry performances throughout Canadian cities. The initiative ran for six months with support from the Canada Council for the Arts. At that time, the network had just formed. Years later, this South-North Griot summit can be considered another part of a long-running dialogue. Included can be conversations about the role of spoken word in our time where protests for social justice overlap. With its ability to capture attention in ways that encourage reaction and response, spoken word is and has always been an empowering method for many performing poets—storytellers whose illuminating editorials offer proof that all lives matter. That affirmation will hopefully extend to the artists’ messages and to the business of their craft. And hopefully arts councils will develop artist-oriented programs of support in response.

I did end up performing “Bittersweet Departure” on a stage as part of a Montréal-based, spoken word collective. Our ambition brought me back to living and my exit, stage left, brought me back to feeling. Best part: I was welcomed into a fold that accepted me and my personal mission to heal. It was a thrilling experience to share with artists and audience a passion for the power of spoken words, together looking deeply into what formed from the impact.

1. “Spoken Word from the North: Contesting Nation, Politics, and Identity” from Flynn, Karen; Marrast, Evelyn. Wadabagei : A Journal of the Caribbean and Its Diaspora 11.2 (Spring 2008): 3-24.

About the Author: Saada Branker

Saada Branker is a writer living in Toronto. She works with emerging writers through Saada STYLO, her copyediting business, and is currently the Fresh Milk Arts Platform Artist-in-Residence in Barbados.